![]()

![]()

GMWSRS

|

(previous newsletters: 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 ) 26 years and counting. Our annual newsletter describes our activities in the previous year and outlines plans for the current year. Table of Contents:

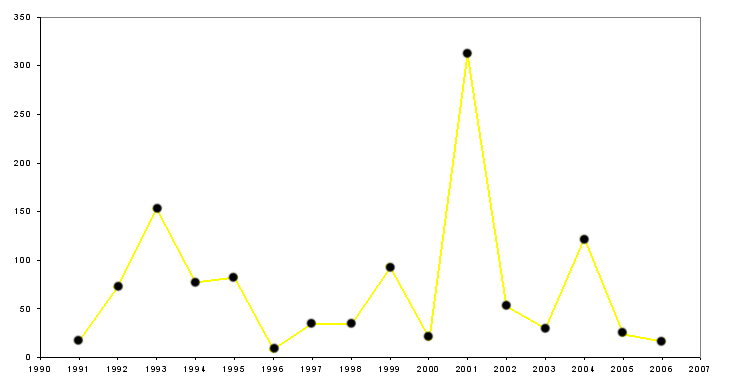

THE SPECTACULAR MIGRATION OF GREATER SHEARWATERS The following article written by Rob Ronconi appeared in Bird Watch Canada. Spring 2007. Number 39. The remains of shipwrecks around the globe attest to the challenges and perils of navigating the world’s oceans. Even with the advent of modern vessels and navigational technologies such as radar and Global Positioning systems (GPS), ships are still stranded or lost at sea. Meanwhile, the enduring seabirds of the world are able to effortlessly navigate and exploit nearly every corner of every ocean. The Sooty Shearwaters of New Zealand are a case in point; they currently hold the world record for the longest recorded animal migration, with a 64,000 km round trip of the Pacific Ocean. With modern tracking equipment now enabling us to follow these creatures on their journeys, scientists are just starting to understand how seabirds undertake these feats. The Greater Shearwater is one of many such mysterious long-distance migrant seabirds. Part of this species’ globe-trekking migratory cycle brings it to its “summer” (actually its winter) feeding grounds off of Canada’s east coast. Although the Greater Shearwater is among the most abundant seabirds in the Atlantic, it is one of the most poorly understood birds in Canadian seas. It nests only in the southern hemisphere, primarily in the Tristan da Cunha island group, but a few hundred pairs also breed in the Falkland Islands. Tristan da Cunha, known as the most remote inhabited place on Earth, is located in the middle of the South Atlantic, nearly 3000 kilometres from any continental land mass. Not discovered until 1506 by the Portuguese explorer Tristao da Cunha, it remained unsettled until 1810 when three Americans called it home for a short period of time. In 1816, the British military took over, fearing that the French would use this island to try to rescue Napoleon, who was being held captive on St. Helena farther north. The community grew slowly, acting as a trading post for passing ships and a monitoring station for U-boats during WW II. Islanders gathered eggs and meat from seabirds, farmed sheep, and developed a commercial fishery for lobster. Now, about 300 people live year-round on the British Overseas Territory of Tristan. The seabirds live mostly on Tristan’s surrounding islands of Nightingale and Inaccessible. Mary Rowan, who led pioneering research on the Greater Shearwater in 1949 and 1950, described Nightingale as a “tussock jungle [that] gives way to grassy clearings, to marshes overgrown with sedge, and to groves of the island tree Phylica nitida” – a shrub-like tree with yellow flowers. Gough Island, some 350 km to the southeast, also provides nesting space for millions of seabirds, including shearwaters, petrels, albatrosses, skuas, and penguins.  The islands of Gough and Inaccessible are now protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and together with Nightingale, provide nesting space for more than 6 million pairs of Greater Shearwaters. Between nesting seasons, these shearwaters undertake an annual northward migration to the North Atlantic; this 12,000 km journey north requires guaranteed food sources where they can regain strength for the long trip home. During their winter (our northern hemisphere summer) Greater Shearwaters can be found across much of the North Atlantic, from New England and the Maritimes to Greenland and the U.K. For the past two years, students and researchers of the Grand Manan Whale and Seabird Research Station have been studying the Greater Shearwaters that forage in strong tidal currents and upwellings around the shoals of Grand Manan Island, located in the Bay of Fundy off the shores of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The birds return to feeding spots predictably with the daily rhythms of the tides. The goals of our research were to answer some basic but important questions. What are these birds eating at tidal upwellings? How much time do they spend at upwelling areas and where do they go between upwelling events? How long do they stay in the Bay of Fundy and what migration route do they take to their distant nesting grounds? The ultimate goal is to piece all this information together and identify critical foraging habitats for these and other seabirds in the Bay of Fundy and elsewhere. When we set out to study the Greater Shearwater in 2005, we were immediately faced with a bigger challenge than expected: how to catch these creatures that seem to glide effortlessly on the slightest wind? Through trial and error we came up with a hula-hoop sized net that flies through the air like a frisbee when tossed. The hoop floats on the surface and a retrieval line lets us pull it, and hopefully a shearwater, toward our boat. This technique, however, isn’t without its challenges. Success depends upon light winds, distracted birds that are foraging in dense flocks, and most importantly, the good aim of a patient thrower. In two years we have caught, without injury, nearly 150 shearwaters. Birds that we catch go through some of the standard protocols of scientific research, which include weighing, measuring, and leg banding each individual. The weight data have been really interesting, showing that birds feeding in the Bay of Fundy pack on weight before their migration south. In late July, when we started catching birds, most weighed between 800 and 1000 grams. By late August, however, many birds were in the 1200-gram range. One individual weighing 1440 grams was so portly that it had trouble taking flight! These energy reserves will be crucial in September when it comes time for them to undertake their long-distance migration. In addition, we collect blood and feather samples that are later processed in a laboratory to tell us what these birds have been eating. So far, it seems that krill and herring make up the bulk of their diet around Grand Manan, but more work is needed before we can say how much krill or how much herring. Interestingly, some individuals appear to specialize on eating krill while others eat mainly herring. The krill eaters were underweight in 2005, indicating that a fat-rich herring diet likely contributes to the much-needed weight gain for migration. We wanted to know much more about the movements of shearwaters, so in 2006 we received funding to attach six light-weight (30-gram) satellite transmitters to the feathers of Greater Shearwaters in the Bay of Fundy. These tags send signals every 70 seconds to a network of satellites orbiting the earth. When the tags and the satellites align just right, it is possible to plot the position of our tagged birds to within 200 metres, depending on weather, satellite angles, and stillness of the birds. Generally, we received about 4 to 10 good positions from each bird every day. The transmitter batteries lasted about 100 days, giving us good location data for over 3 months.  The results from the

first year of our telemetry study were outstanding and kept us on

the edge of our seats every day in anticipation of the next updates on

our tagged birds. We nicknamed our birds Ivan, Robert, Rosa, Kaiva,

Sedna, and Tristao, in remembrance and honour of humanitarians,

goddesses, explorers, and Grand Manan fishermen. Robert was the record

holder, traveling over 32,000 km in 108 days! Nonetheless, the feats

performed by each of the birds were incredible in their own right. The results from the

first year of our telemetry study were outstanding and kept us on

the edge of our seats every day in anticipation of the next updates on

our tagged birds. We nicknamed our birds Ivan, Robert, Rosa, Kaiva,

Sedna, and Tristao, in remembrance and honour of humanitarians,

goddesses, explorers, and Grand Manan fishermen. Robert was the record

holder, traveling over 32,000 km in 108 days! Nonetheless, the feats

performed by each of the birds were incredible in their own right.The birds foraged almost continuously around Grand Manan Island for the entire month of August before their migration south. In mid-September, they traveled across the North Atlantic passing the Azores, the Canary Islands, and the Cape Verde Islands, and headed south along the coast of West Africa until branching west to the coast of South America. About 19 days after leaving the Bay of Fundy they reached the shores of Brazil where they continued their journey south to the Patagonian shelf off the coast of Argentina. They spent another 35 days foraging around the Patagonian shelf before finally heading east to their nesting islands. Five of the six birds arrived at the islands, and some of them, but not all, started what looked like an incubation routine. Unfortunately, just as the nesting season was getting underway we reached the end of the battery life for the tags and the story stops there. We are not sure if these were breeding adults or just immature birds investigating nest sites for future years. For now, however, we have unlocked a few mysteries about the Greater Shearwater including their feeding activities in the Bay of Fundy, the identification of a second important foraging ground off the coast of Argentina, and mapping their migration routes. Our project will continue this summer, with the tagging of more Greater Shearwaters as well as some Sooty Shearwaters. Stay tuned for more spectacular results! Additional information can be found at www.seaturtle.org/tracking (search the archived projects for Tracking Greater Shearwaters), and new daily updates of the shearwater tracking will be posted in August.  UPDATE: In 2007, we did not received sufficient funding to support the level of research undertaken in 2006, and could only purchase two satellite tags. Along with some radio tags, the effort this summer was investigating the effects of tagging on the shearwaters and whether it is possible to relocate tagged birds once they are released, by triangulating positions from the radio signals or pinpointing a location by following the signal via boat. We have confirmed funding from the Baillie Fund and New Brunswick Wildlife Trust Fund for 2007 but any additional funding from donations will greatly help with this year’s field season or can be carried over to next year. Next year is looking more promising. Rob won 3 satellite tags through a satellite tag competition promoted by the Pacific Seabird Group. We are also in a grant competition with the National Geographic Society but are applying for other funds as well. ADDITIONAL SEABIRD WORK: In 2007, working with Robin Hunnewell from the Manomet Center in the U.S., we provided our vessel Phocoena and crew for surveys of migrating red-necked phalaropes, a small seabird that can occur in large numbers in the Bay during their migration. We successfully caught and released the first two red-necked phalaropes at sea. Stayed tuned for our next newsletter for more details. HARBOUR PORPOISES: Begun in 1991, the Harbour Porpoise Release Program is a successful co-operative program between the GMWSRS and weir operators. From 1991 to 2005, we have released more than 800 porpoises from weirs around Grand Manan Island. In 2006 the GMWSRS completed the 16th year of the Harbour Porpoise Release Program with the program beginning in the second week in July with the arrival of the release team on Grand Manan. Formal weir checks began on July 25th and were carried out until September 1st. Sixteen porpoises were recorded in weirs which was similar to the 24 recorded in 2005. Usually entrapments peak in August and this trend was seen in 2006. Of these 16 entrapped porpoises, six swam out unassisted, eight were released and two died while we were attempting to release them. Fishermen released two of the porpoises without our assistance during the summer and amazingly, another eight during the winter and spring either using our standard handling techniques or when the netting was removed and the porpoises swam out. VARIATIONS IN HARBOUR PORPOISE ENTRAPMENTS 1991-2006  Overall, the 2006 season was similar to 2005; many weirs did not fish well, some did not catch a single herring all summer and we saw few porpoises in weirs. It is presently unclear whether the lack of herring in weirs reflects an overall decrease in Atlantic herring in the Bay of Fundy or re-distribution resulting in a lack of build up of herring in any significant concentrations in inshore waters. There is some evidence from the fishing industry that the youngest age classes of herring were extremely strong this year, suggesting that we might see an increase in herring landings and a corresponding increase in porpoise entrapments, in the near future. The continued collapse in herring landings in 2006 is troubling for the weir fishery as a whole but it is beneficial to the conservation of porpoises because of fewer entrapments. Many of the porpoises that were recorded in weirs swam out on their own (38%) and we attribute this to no herring in the weir. In a typical season, each weir would have several hundred tons of fish inside, and we believe that the dense schooling behaviour of the herring may serve to obscure the weir entrance both visually and acoustically. Also when a weir is full of herring, a net is drawn up to close the entrance during the day preventing escape of fish and entrapped porpoises. Additionally in 2006 without herring in the weir the porpoises may have been motivated by hunger to find their way out more quickly. In addition to the porpoises, a single minke whale was documented in a Grand Manan weir in the summer, successfully swept out on August 8th by weir fishermen. On November 5, a right whale was spotted in a herring weir near Deadman’s Harbour. The weir did not have any netting but the stakes were very close together. The Campobello Whale Rescue Team responded after coordinating with us because of our experience with two right whales trapped in a weir here a few years ago. It was suggested that some stakes be removed leaving an open space from the surface to the bottom. Conveniently divers were working in the area and they stopped what they were doing to help. Once the opening was large enough (eleven stakes later) the right whale immediately swam out. A large portion of our success is due to the frequent use of our mammal seines. These nets are used to release porpoises and whales while leaving herring inside the weir. We helped develop the first mammal seine in 1991 and also helped in obtaining the second larger net in 2002. Our data show that porpoise mortality rates are far less when fishermen use the mammal seine (2%) versus a herring seine (11%) so we strongly encourage its use. We have discovered that the two seines are better suited for use in specific weirs and as such guide the fishermen on which seine to use. Together with the help of Grand Manan weir fishermen we successfully released five porpoises during the 2006 season, with another ten released by fishermen without us present (this includes the winter releases and the latest release of two porpoises in June 2007 before our field season begins). With an almost continuous fishing of weirs it is difficult to decide when one season ends and the next begins. We were able to obtain some information from the five individuals we handled. The smallest and largest porpoise this year were: GM0607 (95.5 cm), released from First Venture Weir and GM0606 (149 cm), released from Jubilee Weir, respectively. We clipped small, uniquely numbered plastic roto-tags on the dorsal fins of all five porpoises (white for females and blue for males—we change colours every year); these tags allow us to identify individuals if they are later re-sighted. Several of the porpoises we roto-tagged in previous years were sighted around Grand Manan over the course of the summer. This is an on-going, long-term project aimed at monitoring the health of a wild population of harbour porpoises. The results of the analyses of blood samples from six individuals will go into our data base and will provide a snapshot of the health status of the population in 2006. We would like to thank all the weir operators who worked with us in 2006 and continued to release porpoises after our team left in the fall. Our program would not work without them. THANK YOU to our funding partners in 2006 and those who gave private donations: Ark Angel Foundation, Connors Brothers, Down to Earth Conservation and Education, Humane Society of Canada, Huntsman Marine Science Centre, International Fund for Animal Welfare, Whale & Dolphin Conservation Society. SEASONAL VARIATIONS

IN HERRING LIPIDS Lipids (Fats) in Right

Whale Faecal Material Faecal samples were collected between August and September by the New England Aquarium (NEAq) field crew and the GMWSRS using a fine mesh dipnet on a long pole. Right whale faeces float at the surface for a short while and are usually found because of the odour trails. The NEAq also use a dog that has been trained to locate the faecal odour trail and the dog has been successful from over a kilometre away. Copepods were collected during weekly plankton tows from the middle of July through the end of September of 2006 in the right whale conservation area, using bongo nets (named for their resemblance to bongo drums) towed vertically from the bottom to the surface. A davit and hydraulic hauler were purchased and installed on our research vessel Phocoena through a kind donation from the Canadian Whale Institute.  Copepod samples were identified and counted throughout the summer of 2006 and results showed that no less that 76% of the samples contained the target species of copepods and showed little variation between sampling sites. Copepod and fecal samples were analyzed for lipid class content and composition in the fall of 2006. Copepod lipids were dominated by wax ester components and showed little variation between sampling sites. Faecal lipids consisted primarily of wax esters and triacylglycerols. On average each fecal sample contained less than 50% wax esters and interestingly, most samples were composed of 32% triacylglycerols. Further lipid analysis will be completed by the spring of 2007 to determine individual fatty acids and fatty alcohols in these lipid classes. If right whale metabolic capabilities are similar to traditional mammals, then we should expect higher proportions of wax esters and less, if any, triaclyglycerols in their fecal material. However, if we accept that right whales are utilizing wax esters then we can assume that right whales may have evolved a unique metabolic mechanism, such as specialized enzymatic machinery or a symbiotic bacterial relationship, to utilize some or all of their wax-ester rich diet. Triaclyglycerols, on the other hand, are the primary storage lipid of most mammals and thus it seems wasteful to expel them from the body. It is unclear where the triaclyglycerols in the feces are coming from, although their presence may reflect differential metabolism of triaclyglycerols and wax esters thereby changing the relative proportions we see in the fecal material. This may indicate that right whales are so specialized at metabolizing wax esters, that triaclyglycerols are essentially ignored during catabolism. Alternatively, triaclyglycerols may be endogenous or even a by- product of bacterial breakdown that is expelled from the body. We will be conducting a second Bay of Fundy field season in 2007 to continue the copepod and fecal collection. We will quantify lipid classes in these samples and compare these results to those that were collected during 2006. In addition we will start to further analyze lipid class based on their fatty acids and alcohols. This will provide more resolution to the analysis and will hopefully enable us to draw conclusions about some of the unique aspects of right whale lipid metabolism. We are thankful to the Canadian Whale Institute, the Fairmont Algonquin Hotel, and private donations for funding. Funding in 2007 will be coming from the Fairmont Algonquin Hotel and private donations. Charter services for copepod collection for a Masters student at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Nadine Lysiak, in 2006 also assisted with operational costs. Now that we have the hauler on our research vessel we can provide this service to visiting scientists when requested. Right Whale Stewardship  Data was collected from late May until the middle of October from four whale watch companies in the Bay of Fundy and was contributed to both the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium data base and the Atlantic Canada data base maintained at the St. Andrews Biological Station. The late occurrence of right whales between Grand Manan and the Wolves, along the ferry route and extending as far as Point Le Preau to the northeast and Campobello Island to the southwest, was first noticed by one of these whale watch companies in October. This unusual occurrence of right whales in large numbers in this area lead to a major effort to protect the right whales lingering in the Bay and allow the lobster fishers to set their traps for the beginning of the season in November. The fishers agreed not to set near right whales and to report any sightings so everyone could be notified of where the right whales were located. The Grand Manan Fishermen’s Association established a hotline for sightings and the GMWSRS and Fisheries and Oceans Canada kept the line updated with any sightings. The right whales remained in the area until late November. While right whales do occur in the Bay of Fundy until December in some years, it is usually in the deep waters of the Grand Manan Basin and not along the Grand Manan ferry route. Fishers not familiar with right whales needed information about them which was provided by the GMWSRS to both the Grand Manan Fishermen’s Association and the Fundy North Fishermen’s Association who sent the material out in their newsletters. Working with fishing associations and others we also developed a package of information including a voluntary Code of Conduct for fishermen, information on why right whales are vulnerable to entanglement in fishing gear, and reprinted an identification sheet for the various whales they may encounter. We are hoping that these can be distributed through Fisheries and Oceans Canada and also fishing associations.  We were also able to reprint the colour trip record brochure for whales and seals of the Bay of Fundy with a special section about right whales. This popular brochure is being distributed to whale watch companies and other locations where they may be of interest. We were also able to develop a website for our RIGHT WHALE AODPTION PROGRAM www.AdoptRightWhales.ca. We have four individuals, three mothers and their calves, and three families who can be adopted. Funding for these projects was from the Government of Canada Habitat Stewardship Program for Species at Risk, private donations and in kind support. We would like to thank everyone who donated time and effort to our work and projects including the whale watch companies (Whales-n-Sails Adventures, Sea Watch Tours, Quoddy Link Marine, Norwood Boat Tours), Campobello Whale Rescue, GREMM, Marine Animal Rescue Society, Dr. Moira Brown, Grand Manan Fishermens Association, Hubert Saulnier, and especially Andrea Kelter for hundreds of hours of graphics work. Benoit Latour was contracted for the translations into French and Kerry Lagueux created a range graphic for North Atlantic right whales. Successful Release On 11 September 2006, the GMWSRS assisted the Campobello Whale Rescue Team with the release of a humpback whale entangled in a crab trawl. The fishermen who owned the gear was unavailable to assist but we received permission from Fisheries and Oceans Canada to have another fishermen haul the crab gear to remove the strain from the humpback. After a few lines were cut, the whale was able to swim free of the gear. We would like to thank Jerry and Justin Flagg, Michael Outhouse, Shep Erhart and Regina Grabrovac for additional assistance. Right Whale Notes  <> In 2006, there were 19 calves

born, continuing the above average number of calves born. In

2007, 22 calves were born with the latest occurring at the end of May

off Cape Cod, an abnormally late birth and unusual area. Most

right whale calves are born from North Carolina south to Florida

between December and early March. It is possible that this mother

then took her calf to Florida in July and then into the Bay of Fundy by

the end of August. Since 2001, 157 calves have been born compared

with 101 in the previous period between 1991 and 2000. Not all of

these calves survived but the recent good calving years has resulted in

a growing population, currently estimated at 396 right whales, despite

a number of right whales dying each year from ship strikes and

complications of entanglement in fishing gear. <> In 2006, there were 19 calves

born, continuing the above average number of calves born. In

2007, 22 calves were born with the latest occurring at the end of May

off Cape Cod, an abnormally late birth and unusual area. Most

right whale calves are born from North Carolina south to Florida

between December and early March. It is possible that this mother

then took her calf to Florida in July and then into the Bay of Fundy by

the end of August. Since 2001, 157 calves have been born compared

with 101 in the previous period between 1991 and 2000. Not all of

these calves survived but the recent good calving years has resulted in

a growing population, currently estimated at 396 right whales, despite

a number of right whales dying each year from ship strikes and

complications of entanglement in fishing gear.Right whales continue to be entangled, some for many years. Unfortunately it is not always easy to respond to these whales due to distance from shore, complications of the entanglement and the unwillingness of right whales to be assisted. All of the entanglements are different but usually involve the mouth, flippers and tail to some degree. In early 2007 one male right whale that had been entangled for several years (#1424) was found dead in the Gulf of Maine and despite heroic attempts to track the carcass by satellite telemetry, the carcass was never recovered and cause of death remains unknown. Reduced funding to the New England Aquarium from federal U.S. sources almost meant no Bay of Fundy field season for them in 2007, however, through the efforts of several individuals and commitment of funds from both private and non-profit sources, the research team was able to continue their work in the Bay of Fundy which they have undertaken since 1980. A digital camera was permanently loaned to Laurie from the New England Aquarium so she would be able to collect photographs of right whales including the all important photographs of young calves. By the time the calves come to the Bay of Fundy with their mothers, the callosities on their heads are fully formed and once photographed they can then be followed for the rest of their lives since these patterns remain the same, although the head does grow larger. In 2006 visitor numbers dropped to a ten year low (5372) from June through the first part of October. Ou  r sales per person in the

gift shop, however, continues to climb which is excellent and makes it

possible to pay some salaries and maintain the facility without looking

for outside assistance, even with the declining number of

visitors. We have also had excellent staff Brittney Carro

(partially funded by a grant from Human Resources Canada) and Brenda

Bass, plus our volunteer Ken Ingersoll filling in when Laurie was busy

with other duties. We have received donations of items for sale

from some of our “Friends” including matted

photographs and calendars. r sales per person in the

gift shop, however, continues to climb which is excellent and makes it

possible to pay some salaries and maintain the facility without looking

for outside assistance, even with the declining number of

visitors. We have also had excellent staff Brittney Carro

(partially funded by a grant from Human Resources Canada) and Brenda

Bass, plus our volunteer Ken Ingersoll filling in when Laurie was busy

with other duties. We have received donations of items for sale

from some of our “Friends” including matted

photographs and calendars. We are working on rearticulating the skeleton of a pilot whale calf that stranded in 2003 to add to our display. It has been a challenge because of the young age of the animal and the lack of fusion of bones—a real 3D puzzle without instructions! On 9 May 2007 we received a report of a stranded porpoise which turned out to be a 14’ female pilot whale. The local fish plant kindly donated a boom truck and freezer space to hold the carcass until we can do a necropsy to determine cause of death and collect any other information. This skeleton will also be cleaned and rearticulated in the coming years for the museum.

IN MEMORIAM

THANK YOU for IN KIND

SUPPORT Scientific

Papers, Book

Chapters:

Learned

Societies Presentations

(previous newsletters: 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 )

|